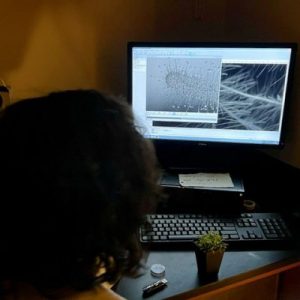

Somewhere deep inside a laboratory on the Syracuse University campus, students gather in a dark room, the only light coming from the glow of a computer. The pixels on the screen visualize an up-close view of a cell, uncovering a striking, never-before-seen image full of vibrant colors. This must be a course just for science majors, right? Think again!

In Bio-Art (BIO 400/600 and TRM 500), cross-listed between the College of Arts and Sciences (A&S) and the College of Visual and Performing Arts (VPA), STEM students join art majors in a first-of-its-kind course at Syracuse, where students explore and create their own bio-art.

Offered for the first time in spring 2022 and co-taught by Biology Professor Heidi Hehnly and Film and Media Art Professor Boryana Rossa, the course included students from VPA, the College of Engineering and Computer Science, A&S’ Departments of Physics and Biology, and from the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry. The unique collaborative structure promotes cross-pollination of skillsets—where scientists gain valuable tools from artists, such as art theory, semiotics, image processing and video editing, and in return artists learn new scientific methods from STEM faculty and students, including microscopy and genomics. The result is visually inspiring art rooted in science that tells a personal story.

The Motivation

Bio-art first came to the University in 2018, when Rossa and Hehnly established the Bio-Art Mixer in collaboration with the Canary Lab in VPA’s Department of Film and Media Arts. The open forum includes faculty, graduate students and members of the general public from different scientific and artistic backgrounds who share innovative research, foster ideas for new art and research projects, and view new science-inspired artworks from leading bio-artists from around the world.

“Boryana and I believe that there is much benefit to bringing artists and scientists together in a public forum,” says Hehnly. Similar to how artists use imagination to conceive ideas for their work, she explains that scientists use creativity and self-expression when developing a hypothesis and carrying out studies.

“Scientific research is a form of creative expression, but much of the time communication of scientific data to the public typically emphasizes utility above aesthetics,” says Hehnly. Bio-art disrupts that notion, celebrating the physical beauty of science while providing a space for productive dialogue.

“Historically, arts and sciences have been always related,” Rossa says. “When an artist employs biological protocols and techniques used in the lab for the creation of an artwork, there are other layers of creative and intellectual exchange opened. Two fields that rarely look at each other are put in the same territory and can observe their field from a very different perspective and rediscover their terminology, which opens a gate for large debates and for collaborations.”

The growing popularity of the Bio-Art Mixer inspired Rossa and Hehnly to organize a class built on the same tenets. Hehnly says the ability to recognize alternative points of view is critical to scientists because it is fundamental for establishing successful communication of research to a wide audience.

“This is specifically important during the pandemic, when many people and societal entities question scientific research dedicated to the disease and to vaccine development,” she says.

The class was a chance for students to not only get excited about the natural world, but also work with their peers to view their own scientific research and art projects through a new and potentially unconventional lens.

Learning the Bio-Art Basics

The semester started with an introduction to the field of bio-art, where students learned about the work of acclaimed international bio-artists. They even sat in on a Bio-Art Mixer featuring Guy Ben-Ary, the inventor of cellF, which is the world’s first neural synthesizer that contains a “brain” made of a biological neural network that grows in a Petri dish and controls in real time an array of analog modular synthesizers.

Rossa and Hehnly also welcomed visiting and showing artists to the class throughout the semester. Students participated in a workshop with artist Adam Zaretsky from Ionian University in Greece. Zaretsky had the class take on the role of bioethicists, science fiction writers and bio-art critics to write a short piece about advances in genetics. They were also introduced to the artist Paul Vanouse’s (University at Buffalo) award-winning work “Labor” 2019, which reflects upon industrial society’s shift from human and machine labor to increasingly pervasive forms of microbial manufacturing. Artist Jennifer Willet also presented her project “Baroque Biology,” a series of photographs in which microbial “actors” take part in “melodramatic ecological interspecies performances.”

After a handful of lectures and artist presentations, students conceived and pitched their own bio-art project ideas to Hehnly and Rossa, drawing inspiration from their journeys as scientists and artists. Their ideas were motivated by their own interactions with nature, perspectives on their own identity, struggles with human disease and their views of humanity, to name a few. Once project ideas were approved, the hands-on work began.

Students used biological samples and techniques that can be found in advanced STEM fields and transformed them into traditional illustrations, paintings or murals.

The students learned the fundamentals of light microscopy in Hehnly’s lab with the help of researchers Mike Bates, Nikhila Krishnan, Favour Ononiwu, Abrar Aljiboury and Debadrita Pal. They captured stunning images from an array of samples, including those found in the natural world, research studies, aspects of their self or medicinal agents that occur every day in their lives. They also had access to advanced microscopy techniques in the Blatt BioImaging Center and in A&S Professor Carlos Castaneda’s laboratory.

Once the microscopy work was done, students took part in drawing classes to illustrate the images they captured in the lab.

“Drawing has always been connected with biology and with other sciences, especially before the appearance of photo imaging,” says Rossa. “The process of drawing is a method of understanding what we see. It is a form of knowledge.”

In addition to helping students shape their projects into visual displays, Rossa instructed them on how to talk about their work publicly—something that may be common for art majors but was a new challenge for the STEM students.

“We had two very different types of presentations, that were nevertheless in a dialogue,” Rossa says. The art by STEM students was based off their original research, engaging general audiences in diverse aspects of science. The art students grew living organisms and used microscopy to explore questions of their interest concerning subjectivity, connection between people and environment, suffering, transformation, joy, identity and more.

The course culminated with the first on-campus bio-art exhibition at Syracuse that was part of a series titled “Chimera.” In Greek mythology, Chimera is a hybrid consisting of a lioness’ body, a head of a goat protruding from her back and a tail ending with a snake head. Rossa says this title embodies the chimerical manner in which arts and sciences contribute to each other in the displayed projects. The exhibition was on view in the Shaffer Art Building in April.

An Inspiring Journey

Renita Saldanha, a graduate student in the Department of Physics, was intrigued to see how peers from different disciplines view the scientific images she works with on a daily basis.

“It was really fascinating for me as some of my colleagues from the course saw some details in the microscopy images which I generally miss out on because it may not be very important from a scientific perspective,” says Saldanha, whose physics research focuses on vimentin intermediate filaments, a network of proteins in the cell that protect the nucleus against deformation during cellular migration.

Saldanha’s project, titled “The Lab Notebook,” presented a behind-the-scenes look at a scientist’s diary—the daily log a researcher keeps which notes details of their experiments, successes and failures, and the progress that may lead up to an exciting discovery.

“The bio-art class allowed me to talk about the life of a researcher and the thought process which goes into building up a new idea,” she says. “As a passionate microscopist, I wanted viewers to appreciate the beauty of fluorescence microscopy, where you can visualize a cell with sub-micron-level (less than one millionth of a meter) detail.”

Saldanha’s project included two parts. The first was an excerpt from her written log noting her daily lab activities as well as ethical dilemmas that may arise while using live cell line cultures in research.

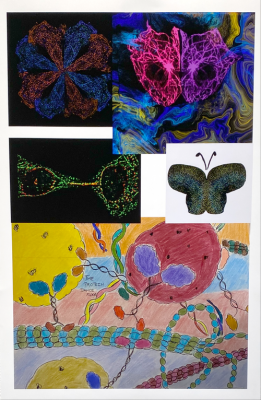

The second part of Saldanha’s exhibition was a compilation of vibrant artworks of various shapes and colors that emanated from images captured by high-powered microscopes. Works included a collection of cells arranged as a symmetric flower with fluorescently labeled microtubules, microtubules in a cell arranged in the form of a mask, an image of a dividing cell with fluorescently labeled vimentin filaments and an original drawing of a motor protein transporting cargoes along the microtubules inside the cell, which she describes as a “molecular dance floor.”

The Body as a Landscape

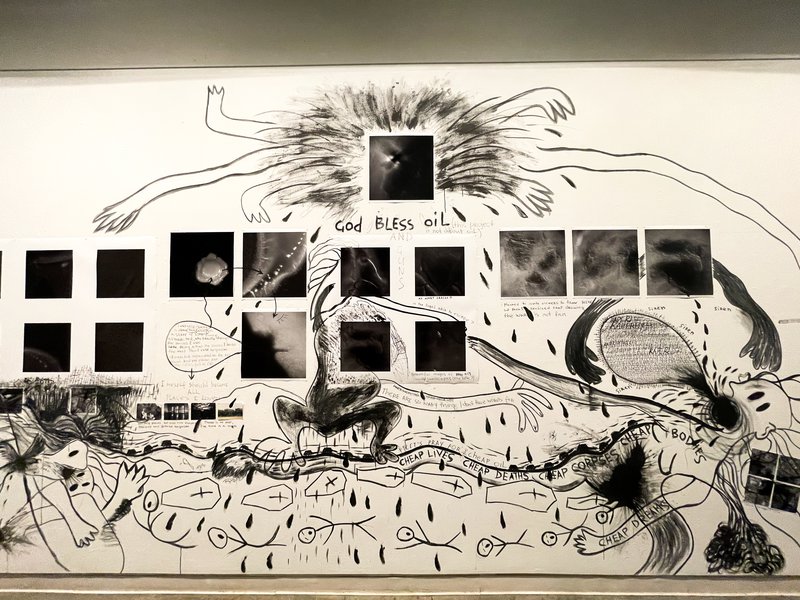

For Oksana Kazmina ’24, an art video major in VPA, her mural titled “Dead(ly) Landscapes or I Myself Should Become All Places I Loved” depicted her body as a landscape, examining how the war in Ukraine and destruction of lands affect personal identity. The work was based off her personal artistic interest in exploring the human body as an unfolding event, conditioned by culture, class, geography, gender and other factors while also versatile and able to shift.

Her project was inspired by images of bacterial colonies she captured from her body using high-powered microscopes in the lab. “The photographs reminded me of a photo of landscapes in Ukraine taken by military drones,” she says. For Kazmina, the dark and desolate images of bacterial colonies bore a marked resemblance to images illustrating the stupefying destruction and scorched landscape in Ukraine.

“The war (in Ukraine) is stealing our landscapes as a lot of places will be inaccessible for years due to the mines, while others are taken or erased,” says Kazmina, a native of Ukraine. “War is also stealing our time. When objects, places and people are destroyed, killed or violently extracted, emptiness is created instead.”

Kazmina says observing the daily growth of her bacterial colonies is confirmation that time exists, and that the physical and emotional emptiness in the wake of war is not permanent. Her mural mapped the journey of her mind through her body in what she refers to as an imaginary walk— a sensual experience of recognizing and remembering places and yourself in the places.

“Identity, which is a sum of some repeated bodily practices, rituals, experience, embodied memory, relation to space and time—past, present and future—all of this becomes emptiness [during war],” she says. By evoking memories through her art, Kazmina explains that her project is a way to affirm personal identity.

Diverse Perspectives

According to Hehnly and Rossa, one of their favorite aspects of the class was observing the dichotomy between how artists and scientists viewed and analyzed images. They say lively discussions would often arise among students concerning what “life” is or if scientific images are randomly colored or carry certain cultural, psychological or even physiological bias.

Hehnly recalls a moment of collaboration between a graduate VPA student and an undergraduate biology student who were imaging their samples together that exemplifies the goals of the course.

“Both (samples) were visually beautiful under the microscope, and the students were discussing their perspectives on how it looked and what it could mean, while also helping each other obtain images from their studies,” says Hehnly. “As a microscopist, there’s something special about showing your samples of an image that you may have never seen before. When you can share this experience with someone else that is experiencing the same thing it can induce an infectious excitement for understanding and visualizing the natural world. These are the interactions that I treasure from courses like this.”

Hehnly and Rossa are hopeful to once again offer the class in spring 2024 and encourage anyone interested in learning more about bio-art to attend an upcoming Bio-Art Mixer.

The bio-art exhibition and class were supported by a CUSE Seed Grant, the Department of Film and Media Arts and the Department of Biology.