Biophysicist Alison Patteson is using a trio of grant awards to probe the mysteries of complex living systems.

No one was more surprised than Alison Patteson when, at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, she received her first major National Science Foundation (NSF) grant award. “Frankly, it was a shock to me because some of the work is out of my comfort zone,” says the assistant professor of physics, who is using the funding to study the cellular entry of SARS2, the virus responsible for COVID-19. “I’ve had to pivot my research to accommodate the project.”

But then came two more NSF awards in the space of weeks. For any professor such a trifecta is impressive, even during ordinary times. Amid a recession? Practically unheard of.

“Alison is one of the most creative, adventurous researchers I know,” says M. Lisa Manning, the Kenan Professor of Physics in the College of Arts and Sciences and director of Syracuse University’s BioInspired Institute, where Patteson carries out much of her work. “She’s also an outstanding teacher who uses active learning strategies to reach a broad range of students.”

This variety of students includes Merrill Asp, who became one of Patteson’s first graduate students after her arrival on campus in 2019. He marvels at how she effortlessly juggles high-end research projects while heaping attention onto individual students. “She brings out the best in people, from colleagues and research assistants to undergraduates and high school teachers,” says Asp, adding that his mentor is the product of a “rich and varied” intellectual background.

Indeed, Patteson’s training in physics, mathematics and mechanical engineering makes her well-suited to the BioInspired Institute’s interdisciplinary faculty, who confront global health challenges through research into complex biological systems.

Says Jennifer Ross, professor and chair of physics: “She is preparing the next generation of researchers. These students will have the skills and training to address major challenges of the future, especially involving disease and personalized medicine.”

Recently, Patteson spoke with us about the work that inspires her.

Congratulations on your three NSF grant awards. Would you say a little about each project?

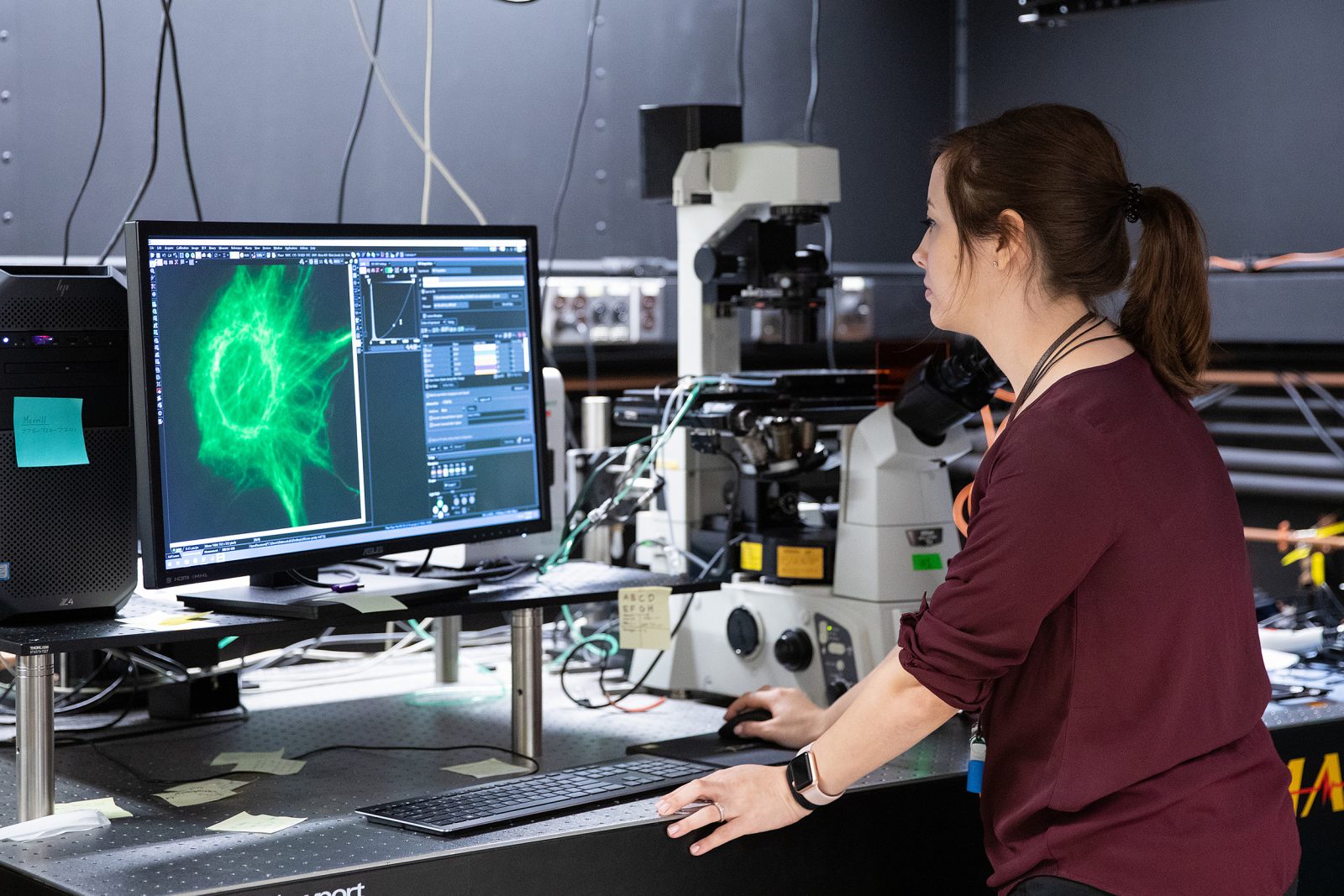

My first project is part of NSF’s Rapid Response Research initiative. Since March, Jennifer Schwarz [associate professor of physics] and I have been studying the cellular uptake of SARS2. Most of our focus has been on vimentin, a polymer found inside and on the surface of the cell that protects the nucleus from SARS2 damage.

The second is funded by an NSF EAGER [EArly-Concept Grant for Exploratory Research] award. Biology professor Roy Welch and I are looking at Myxococcus xanthus, a type of bacterium that exhibits self-organizing behavior in response to external stimuli. We use an array of 3D-printed microscopes to examine dramatic, emergent collective behavior, such as swarming and predation.

My third project involves biofilm growth, in hopes of figuring out why microorganisms stick together on different surfaces. This research has implications for the design of surfaces that could enhance or suppress the spread of biosolids. For instance, nobody wants a medical device or implant covered with bacteria.

What is unique about your research?

Most of it involves complex biological systems at the cellular or molecular level. I am interested in how the cell figures out where it is and what it wants to do. We generally understand how biochemical networks function in the cell. What is less known is how the cell responds to these biochemical cues—and why. That’s where I come in.

It’s exciting to work at the nexus of different fields, some of which are under-explored. I draw on several areas—physics, biology, math and engineering—to understand how systems work and can be applied to societal problems.

Did you always want to be a scientist?

I had a high school teacher who encouraged me to study math and physics in college. Afterward, I had several great mentors who guided me along the way. I took a winding road as an undergraduate before completing graduate work in mechanical engineering at the University of Pennsylvania. Being interdisciplinary has made me a better scientist.

Why is scientific literacy important?

It develops critical thinking skills, which are necessary for any career path. The more we know about scientific processes and concepts, the better decisions we can make as a society.

How has the pandemic impacted your work?

I love being in a dynamic lab environment, so having to socially distance and conduct meetings via Zoom is an adjustment. With some student projects, I’ve had to shift from experimental research to analysis and computational work.

Everything is a balancing act. What we do in the lab is a marathon, not a sprint.

Do your students ever remind you of yourself?

Definitely. Some remind me of how shy I used to be; others, of how I like to be independent. What brings us together is an innate sense of curiosity.