Biology Professor Jessica MacDonald has received a grant from the National Institutes of Health to investigate maternal folic acid’s role in promoting healthy brain development.

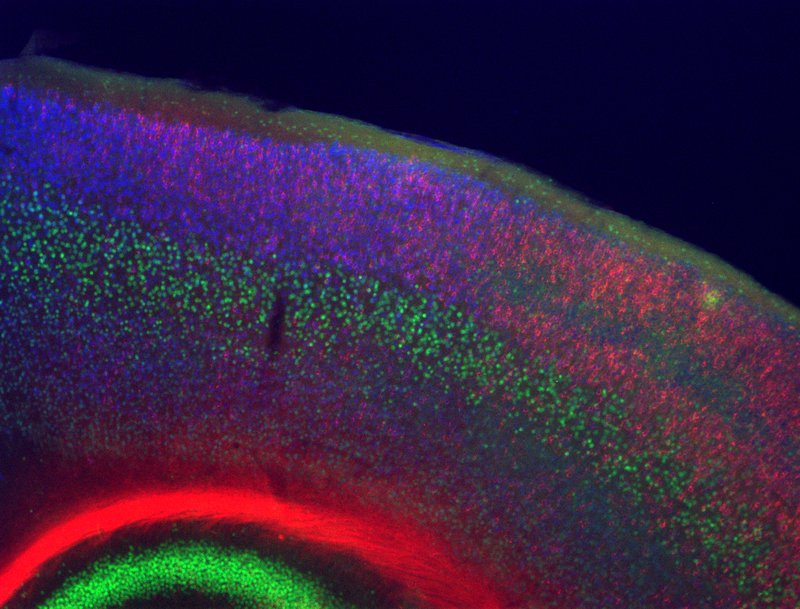

The neocortex, or “thinking brain,” accounts for over 75% of the brain’s total volume and plays a critical role in humans’ decision making, processing of sensory information, and formation and retrieval of memories. Uniquely human traits such as advanced social behavior and creativity are made possible thanks to the neocortex.

When development in this area of the brain is disrupted, it can result in neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorders, intellectual disability and schizophrenia. Researchers have not yet identified the precise causes of this atypical development, but they suspect it likely involves a combination of genetic and environmental factors, including maternal nutrition and exposures during pregnancy.

Jessica MacDonald, associate professor of biology, has received a two-year grant from the National Institutes of Health to investigate the effects of maternal folic acid supplementation on neocortex development. According to MacDonald, this study was motivated by past findings indicating that folic acid supplementation during the first trimester can significantly reduce the risk of neural tube closure defects, such as spina bifida, in children. When the neural tube of the fetus does not close correctly, it can lead to improper development of the brain.

“In countries where cereals and grains have been routinely fortified by folic acid, the incidence rate of neural tube closure defects has dropped 30% overall,” says MacDonald. “Whether folic acid supplementation prevents a neural tube closure defect likely depends on the cause of the disruption in the first place and whether it is due to a specific genetic mutation.”In previous studies, researchers tested mice with certain genetic mutations that developed neural tube defects. Mice with a genetic mutation in an epigenetic regulator called Cited2 showed a decrease in the incidence rate of neural tube closure defects from around 80% to around 10% when exposed to higher maternal folic acid during gestation.

MacDonald’s team will now explore whether maternal folic acid can also rescue disrupted neocortical development in mice as it does for the neural tube closure defect.

“Our preliminary data are very promising that this will occur,” says MacDonald. “There are a growing number of studies indicating that maternal folic acid supplementation at later stages of pregnancy can also reduce the incidence of neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders in children, including autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia. Other studies have shown that too much folic acid, on the other hand, can be detrimental. Again, this likely depends on the genetics of the individual.”

MacDonald will work closely with both graduate and undergraduate students in her lab as they seek new insights into how maternal folic acid supplementation alters neocortical development and how it could tip the balance between typical and atypical neurodevelopment. This project will be spearheaded in the lab by graduate student Sara Brigida.

– Dan Bernardi