Shikha Nangia and her student researchers are advancing efforts to find cures for debilitating brain diseases.

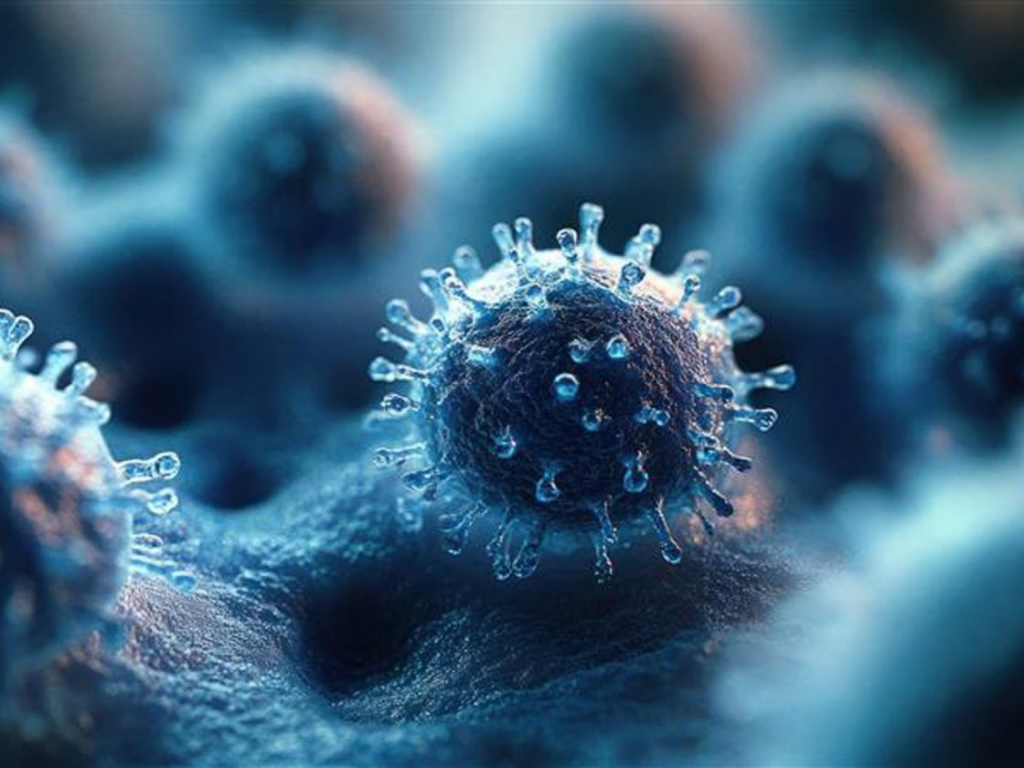

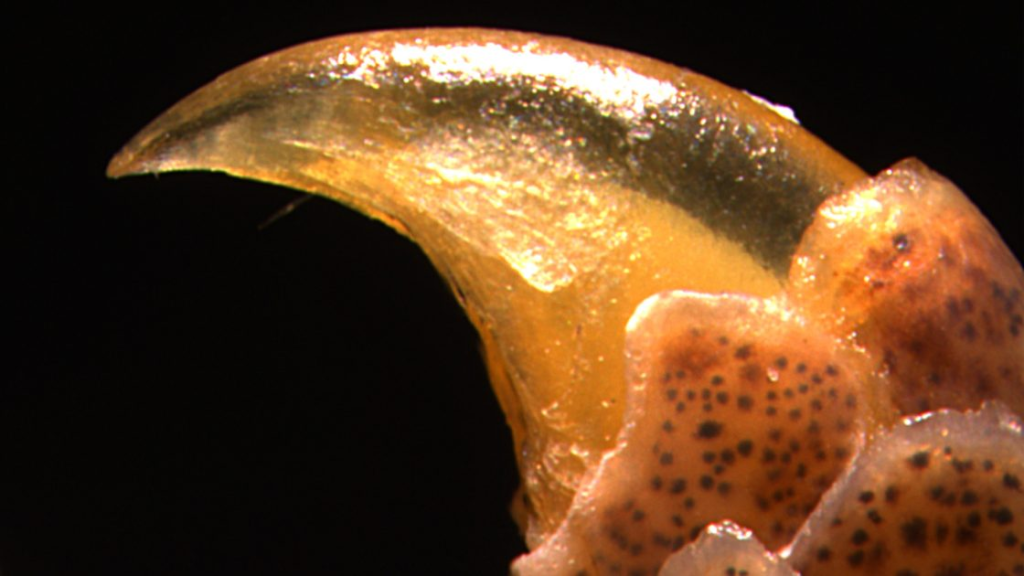

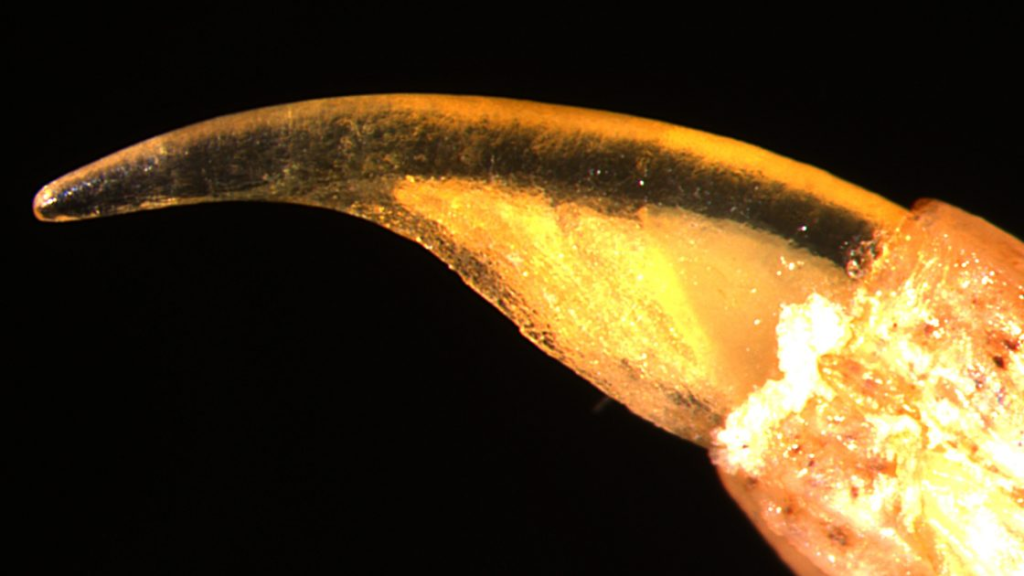

The blood-brain barrier is a tightly locked network of cells that protects and defends the brain from harmful substances and pathogens that could cause damage. While this barrier serves to protect our brains, in the case of finding cures for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, the blood-brain barrier has been a big obstacle.

Enter research from Shikha Nangia, the Milton and Anne Stevenson Endowed Professor of Biomedical and Chemical Engineering and department chair in the College of Engineering and Computer Science.

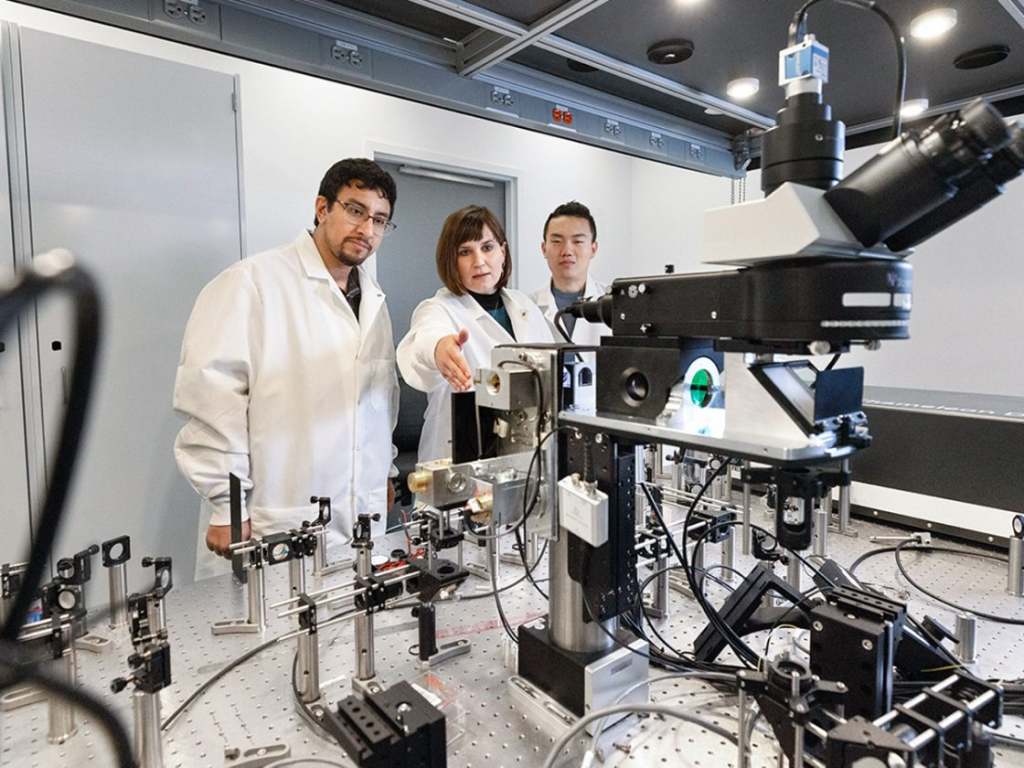

Working with undergraduate, graduate and postdoctoral students, the Nangia Research Lab uses theoretical and computational techniques to determine how to best enable the transport of drug molecules across the blood-brain barrier.

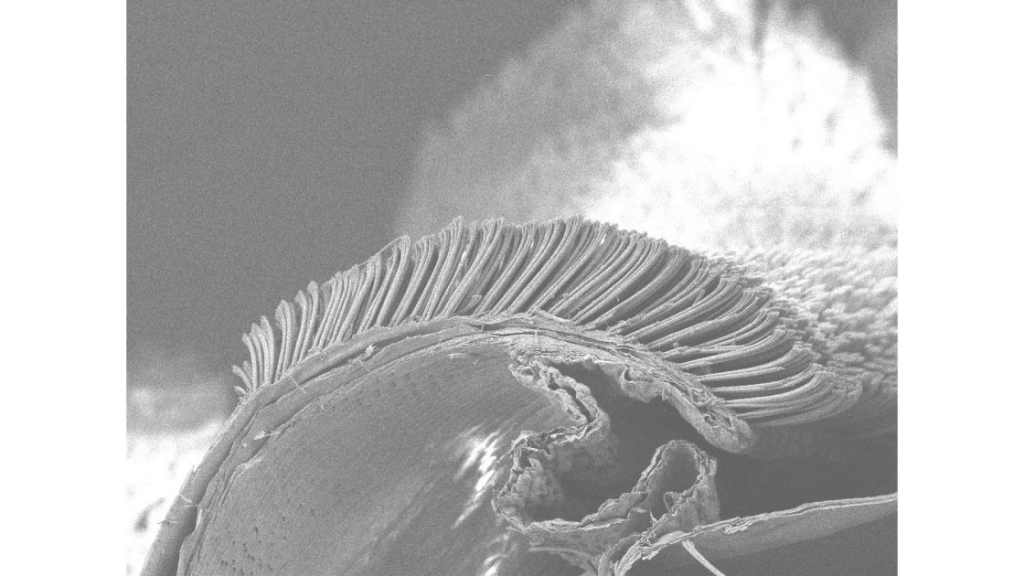

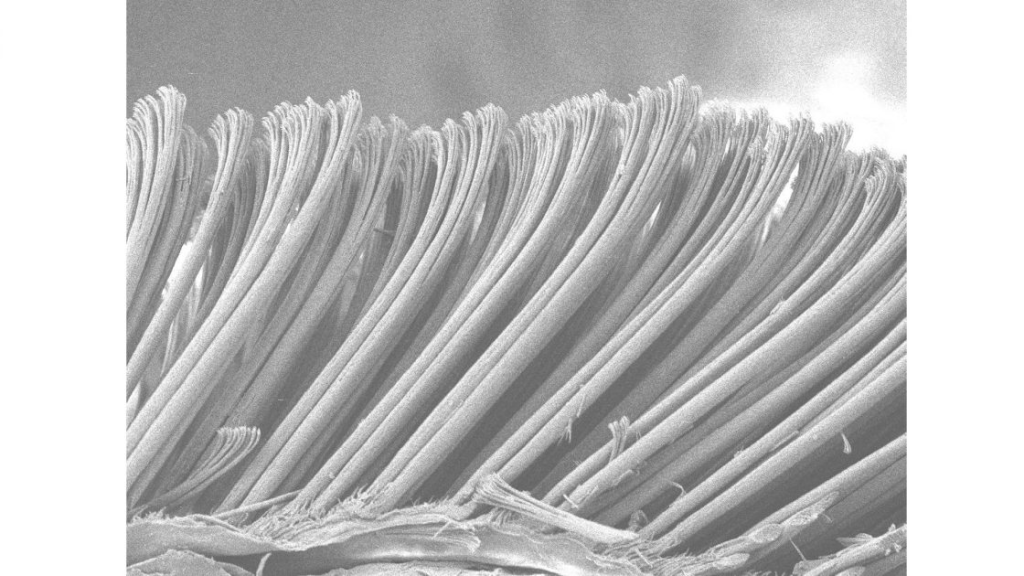

Nangia’s research led to the creation of the first molecular model depicting what the blood-brain barrier looks like, which has proven helpful in identifying what can and what cannot pass through the narrow tunnel into the brain.

Understanding that Alzheimer’s and cancer treatments are too large to pass through the blood-brain tunnel, Nangia’s group is advancing research to find a cure for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

“We cannot break the blood-brain barrier because it’s essential for our survival,” Nangia says. “The trick is, how do you modulate the blood-brain barrier, so it becomes a little bit larger when the drug molecule goes through, but then closes back and becomes small again after the drug has gone into the brain?”

Engineering Solutions to Diseases That We Cannot Cure Easily

As a biomedical and chemical engineer, Nangia is using her research to devise new ways to “engineer solutions to diseases that we cannot cure easily.” Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s certainly qualify, and Nangia is familiar with these debilitating brain-related diseases. A few members of Nangia’s extended family suffered through Alzheimer’s, and those experiences watching loved ones lose themselves and forget their identity had a profound impact on Nangia’s studies.

“In every situation, you see someone you knew very well, and you lose that person gradually over time,” Nangia says. “Out of the top 10 leading causes of death in America, Alzheimer’s and other brain-related diseases is the only one where there is no cure. That motivated my research.”

Nangia and her students examine the interface of the blood and the brain cells using computational models of the brain, building upon the complex experimental research that has gone on for decades.

With a big assist from the Research Computing group on campus, which provides state-of-the-art computer facilities, the Nangia Research Lab runs simulations over time that help better understand why certain molecules like water, alcohol and caffeine can successfully pass from the bloodstream into our brains, while cancer treatments are unable to penetrate the barrier.

“To devise a treatment, we would have to either push the tight junction walls of the blood-brain barrier to make it bigger for a bigger drug molecule to go through to the brain or modify our drugs to be so small that they’re at the same order of magnitude as a molecule of caffeine, which can pass through the tunnel,” Nangia says.

Next Steps for a Cure

The next steps leading to a cure involve taking the models created in Nangia’s lab and, collaborating with researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, the University of Michigan and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, examining the effectiveness of these models through testing on mice.

Using the same modulators utilized on campus, the tests will expand the subject’s blood-brain barrier to see if the injected substance can successfully pass from the bloodstream into the brain. If the intended results can be achieved, next steps include thinking about widespread clinical trials and, eventually, obtaining approvals from the Food and Drug Administration.

“It’s a long road to a cure, but it starts with the first fundamental understanding that we obtained through our models,” Nangia says.

Research Success Hinges on Students

Since coming to campus, Nangia has taken great pride in mentoring more than 100 student researchers, from undergraduates and master’s students through doctoral and postdoctoral students.

The students come from different backgrounds ranging from biomedical and chemical engineering to biology and neuroscience. Since computational modeling sits at the intersection of multiple disciplines, Nangia says interested student researchers need only bring a willingness to contribute and her lab will have students contributing within two to three months.

“The students’ contributions are critical, because all the work we’ve been doing is all dependent on our students,” Nangia says. “The success of this research program lies on the shoulders of the students who have gotten involved with our lab.”

Once they graduate, Nangia says her researchers have found work in the pharmaceutical industry, in the research and development fields and by applying their computational skills to help companies design new drugs.

After completing a Ph.D., Nandhini Rajagopal G’16, G’21, one of Nangia’s student researchers, started working with antibodies to apply a different perspective to treating Alzheimer’s and other brain-related diseases. Now, she is a scientist at Genentech leading the company’s computational modeling efforts.

“The tools that she’s using she learned at Syracuse University through the research computing environment she was in,” Nangia says. “She’s been able to make a difference in the real world for a company that is strategically examining the blood-brain barrier.”